I was only seven years old when teachers at my school decided to celebrate Christmas by putting on a traditional performance of a Nativity play in our school theatre and cast me in the role of King Herod. Why King Herod? Perhaps, because at that time I was quite tall, had a loud voice and already showed signs of a bad character.

I remember that the play was very well received by the audience who consisted mainly of other, perhaps less artistically talented pupils, parents and some teachers. I was fully convinced that it was my performance as King Herod which was mainly responsible for this success. Unfortunately there are no press reviews left to prove that I was right and I think that the main reason was the fact that they were never written. Today it is difficult for me to judge whether I was a good or bad actor but I remember that after that brilliant debut I was never asked to act in any play again. Of course, I don’t know why. It took almost seventy years until Barbara Chodacki rediscovered my acting talents.

This evident lack of success on the stage didn’t affect my interest in the theatre and for the rest of my life I remained an ardent theatergoer. It also didn’t affect negatively my early years because soon a new hobby appeared on the horizon of my artistic interests. In time it became the main one, and as such survived until now. It was Music.

At first it was only cultivated at home. I think that I should remind readers that my childhood coincided with the war years and the German occupation. Playing music or listening to it was possible only at home and only pianissimo. You didn’t want to attract the attention of the police. The Germans confiscated all radio sets. Television, although already invented was still at an experimental stage. Theatres, opera houses and concert halls were closed and no public concerts were allowed. At night, there was a curfew and in the evenings electricity cuts were almost the rule. There was a shortage of food and other basic goods.

What could you do during these dark, gloomy and cold evenings? You could sing or rather hum. Although many years have since passed I still have vivid memories of those musical evenings at home, where members of our family and close friends gathered and sung together. I remember those beautiful songs and all their words, nowadays usually forgotten.

Another source of music in my childhood home was an old wind-up record player. We had a modest collection of records of different kinds of music but mainly of Italian operatic arias sung by famous Italian tenors. Because of the limited numbers of those records, which we played almost every day, I memorised the Italian texts of all of them and even now, I still know them by heart though I do not speak Italian. I shared this interest in music with my older sister. Our parents, who always made it a priority to meet the needs of their children, suggested that we should start to learn to play the piano.

This suggestion was accepted by both of us enthusiastically and soon a small upright piano arrived at our home and remained with us for many years.

The custom of teaching young children to play the piano is widespread in my country which is not surprising given that Poland is the homeland of Chopin, one of our most famous composers, and in addition we have had, and still have, a whole galaxy of outstanding performers of his music. Thus from childhood on we all strum away on the piano in the hope that some new Chopin will emerge or at very least to prevent any talent going to waste. Therefore, we carry on banging away usually for a few years because, after all, nobody knows when our great and deeply hidden talents will one day emerge to universal acclaim.

How many years we should do it for is a good question.

Internet “piano experts” say that ten thousand hours of practice over a period of five to ten years are necessary to achieve the level of a good professional pianist, depending on the individual degree of intensity of practice. It is worth noticing that they say nothing about musical endowment – perhaps because of political correctness. In fact, young pianists usually practice five hours a day rising to seven a day before an examination or competition. Of course, there are also different opinions about this matter.

Of course, there are also different opinions about this matter.

Fritz Kreisler, the famous Viennese violinist and composer was once asked how many hours a day he devoted to practice. “I don’t practice at all. Practice is only for those who lack talent” was his answer. Musical talents reveal themselves at a very young age. Artur Rubinstein said that he taught himself to play piano before he could speak. Statistics from music school in the USA show

that 80% of their graduates could play the piano by the time they were between four and six years old.

In my case I started my piano lessons at the age of ten. The first year was a great success. I made very fast progress. My teacher was very happy and I was very proud of myself. Later on as my repertoire became more and more technically demanding I experienced many serious difficulties. Among them I noticed, for example, that my left hand was always slower than the right one. Sometimes I felt some cramps in my right fingers or if by mistake I pressed a wrong key the musical dissonance made me shudder. Instead of ignoring it I stopped playing for a short moment until I recovered. The advice of the teacher was only to practice longer every day. The change of teachers didn’t help. Of course I never practiced five hours a day. It was impossible. The school had its own increasing demands and there were other things to occupy my time. One of them was listening to good music. The war was over and in the ruins of Warsaw soon theatres, opera houses and concert halls were being rebuilt and with them there was an explosion of cultural life, so badly suppressed during the years of German occupation. I enthusiastically attended all concerts of classical music and operatic performances. It enriched my love and knowledge of music. Soon I realised that I would never be able to play the piano like those famous piano virtuosi I had an opportunity to listen to and enjoy so much.

Under pressure from my parents and piano teachers I continued torturing myself (and my neighbours too) a little longer, though my sister had stopped many years earlier. They tried to convince me that even if I could not be a professional pianist or piano teacher (yes – those who can, do; those who can’t, teach) I could still play the piano for my own pleasure.

Playing the piano for one’s own pleasure brings me to my next point. In fact, this doubtful pleasure is usually confined to a small group of friends, often the family circle where our amateur pianist plays a few popular songs and dances and even attempts some popular pieces of classical music, done to death in simplified versions. His playing is full of mistakes, there is no attempt at nterpretation, he keeps the sustaining pedal permanently depressed to produce more sound, his rule is “the louder - the better”, and besides, it hides his mistakes.

You would need to have enormous self-confidence and very little musicality to take any pleasure whatsoever in this sort of playing. Certainly, for me it is not music, it is murdering music and \I will never take part in it. I had much higher expectations of music. Occasionally you might hear an amateur pianist whose playing is acceptable and whose pleasure you can share. But even so, there exists a large gulf between the playing of such a person and the skills of a concert pianist.

So, after almost six years of learning how to play the piano I came to a final decision. I stopped my piano lessons and promised myself never to touch a piano again and I kept my promise. It is my view that only young people with exceptional musical talents should undertake learning to play the piano – and there is no lack of such people worldwide.

This personal fiasco as a pianist gave me more time to cultivate music. I devoted some of that previously wasted time to great music performed by acknowledged masters, mainly by attending live concerts whenever the opportunity arose, listening to recorded music and also by reading suitable books about music.

But my contact with music was not entirely passive, because I have always had from my early years a great love of singing. I sing at home and of course also in the bathroom, where the amplifying acoustics enable people even with the modest of voices to enjoy their own wonderful vocal performances.

I sang in the school choir and later in other well known choirs and sometimes even as a soloist. When I became a medical student I took singing lessons for more than two years which unfortunately didn’t raise me above the level of amateur status.

Although my secret ambition had always been to become an opera singer I had the chance to sing in a real opera house only once in my life. It was a special performance given by the Warsaw

Opera in honour of one of its tenors – Jerzy Granowski, who was celebrating the thirty-fifth anniversary of his singing career. In that performance he sang the leading role. At the end of the opera, he received a standing ovation, flowers, speeches etc and the whole audience sang for him the traditional and popular Polish song: Sto lat, sto lat…, which means they wish him one hundred years of life in good health etc, etc. The song can be considered, to a certain degree, as an equivalent of the equally popular English song: For he is a jolly good fellow…. As I was a member of the audience, I sang the song together with all of the rest and it was the only performance I had sung in an opera house in my life.

Clearly, that one performance in an opera did not satisfy my vocal hunger but I was lucky and soon found another place to sing. Although it was not an operatic theatre, it had a similar name – it was called an operating theatre.

I don’t think many people know that some surgeons have a habit of singing in an operating theatre and perhaps will not be too happy to learn about it. Maybe it should remain a professional secret. On the other hand I believe that explaining fully how it works will bring more understanding from the readers (and potential patients) and maybe, even some acceptance.

Firstly, not all hospitals have their “singing surgeons”. You can find them more commonly in smaller hospitals than in major ones, with many big operating theatres and a factory atmosphere. The basic task is to find a group of colleagues who are responsive to music and like singing together. I would say that in my very long professional career during which I have worked in many hospitals, in six countries and on two continents, I was very seldom deprived of the pleasure of singing in an operating theatre. If this habit had not yet been established in some of them, then it was soon introduced by me.

Secondly, we don’t sing in operating theatre as soloists, but always in a small group, always pianissimo and never during the operation itself but before it, when preparing for it and scrubbing up. I found some hospitals where, at the request of surgeons and operating staff soft music can be played through permanently installed loudspeakers during the operations. I hate this habit. It distracts my attention and if it is music which I particularly don’t like, it will irritate me.

Try to imagine for yourself the following scene in an operating theatre. Three surgeons are scrubbing up for an operation. Dressed in greenish or bluish T-shirts and trousers faded from frequent washing, with white rubber high boots on their feet, masks on their faces and caps on their heads, they don’t look like doctors on TV screens or from your personal contacts. I am one of this troika. We are tired because last night we performed two long urgent operations. We also know that the one we are now preparing for will also be long, difficult and exhausting. Through the glass in front of us we can see the operating room, the patient on the table and the anaesthetist who is just intubating him. The theatre-nurses are bringing their trolleys with instruments closer to the patient. Then, spontaneously one of us starts singing, or rather humming some melody, soon followed by the rest of us. It should be a quiet and slow melody, something like, for example the Chorus of Slaves from Nabucco by Verdi, which I found to be suitable under the circumstances. The music is performing a miracle. Our tiredness has simply disappeared; we are relaxed but concentrated and invigorated. Singing together creates a feeling of some kind of unity and goodwill between us and we become sure that we can fully rely on each other. Perhaps some ancient warriors had similar feelings when singing or praying together before a battle.

Of course, I must stress that this type of vocal activity was only a very marginal part of my whole vocal career which has been developing very slowly and I think that the main reason for my lack of outstanding success was that I have never possessed a really good voice. It was a typical “small voice”, with a narrow range, not really strong enough, nor did it sound very pleasant, all of which thwarted my ambitions to be a successful amateur singer. There’s no great secret in being a great singer if you have a good voice. If you have an exceptionally beautiful voice, you don’t need to work very hard to charm the audience. You can perhaps grab a telephone directory; open it at random and start singing page by page. I am sure it will be wonderful music and your audience will lap it up.

However, if your voice has some limitations it requires hard work to overcome them or at least conceal them, which is not always possible. Some songs will need to be transposed to a more comfortable range. Other more vocally demanding arias must be simply rejected as not suitable for your voice. You should avoid choosing well-known songs performed by the best singers in the world as you cannot compete with them. You should always try to create your own, original interpretation of well known songs. You can also try to improve your performance by using non-musical means like clear diction, gestures and facial expressions and establishing a good rapport with the audience.

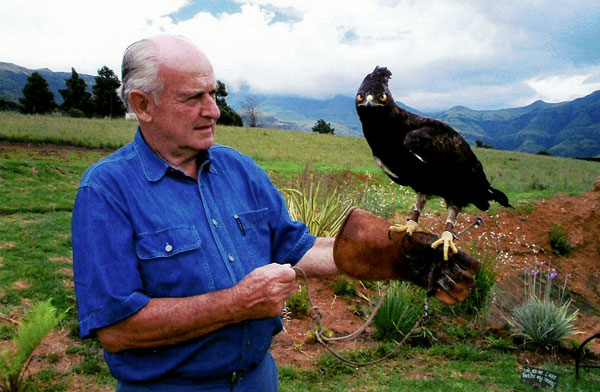

Following this advice I eventually became quite a successful and even popular amateur singer. It happened when I left Poland for good and moved to the African continent where I worked as an orthopaedic surgeon in different countries. There were no musical theatres there and no professional singers or musicians. Instead, there were large groups of expatriates from different countries and cultures working as advisers and experts in different fields. Among them were always some with outstanding musical abilities. They spontaneously organised themselves into groups and were very active in promoting cultural activities in places where they did not exist before.

So in bigger towns we had an amateur theatre, a choir, a symphony orchestra and a group of soloists – instrumentalists and singers – and I was one of them. We gave many public concerts, which enjoyed enormous popularity, perhaps because of the scarcity of similar events.

At the end of my vocal career I had more than fifty songs, operatic arias and duets in my repertoire, and in four languages, which is not bad at all for an amateur singer. Sometimes I even had doubts whether I might have been more popular in some places as a singer than as a doctor. The following, event which took place in Gabarone, the capital of Botswana, will illustrate this doubt.

One day three good-looking ladies arrived at my hospital to see me. They introduced themselves as representatives of the Christian Women Association “Corona” and asked me if I could give a concert for their members. I had never heard of such an association before but my immediate answer was “yes, with pleasure”. The concert would take place in one of the local schools which had all the facilities for the event, and they assured me that they would take care of all the technical aspects of the concert for which they had had previous experience. I telephoned my pianist to ask her to be my accompanist; she agreed and suggested a rehearsal at her home two days before the concert. It took no more than twenty minutes to settle all the details. They asked me to keep the length of the event rather short – less than one hour and without an interval because moving too much might be uncomfortable for some of the persons in the audience who were physically handicapped.

On the day of the concert I was slightly surprised on entering the auditorium to find that the average age of the audience was well over eighty. I felt that I was in an old age home or frail care ward. This didn’t put me off at all; on the contrary, it could work to my advantage. People at this age usually suffer from poor eyesight so they might find me attractive, which would increase my chance of success. So I started singing but found the atmosphere rather lukewarm. Maybe they were also deaf, I thought. I received applause after each song but it seemed to be slightly anaemic. But on the other hand, I consoled myself that one could not expect old ladies to clap their rheumatoid hands too vigorously.

Otherwise, the concert was going smoothly until the last song, the Don Juan Serenade by Tchaikovsky, which is a fast and lively song with quite difficult piano accompaniment. At the end of the song, when Don Juan is calling his Nisetta to come to the balcony, there is a very high note, which should be taken fortissimo. I sang this successfully but just as I hit the high note a lady sitting in the front row fell off her chair.

The pianist was still playing when I jumped down from the podium to help the poor woman. I put her back on her seat and at the same time gently checked her rotation movements of both hips, because I was afraid that she might have sustained a fracture of the neck of the femur. The movements were painless and it seemed that her fall was fortunately a “soft landing”. I promised to visit her at her old age home that evening to examine her more carefully. The woman sitting next to her explained that her neighbour was deaf and should not come to concerts but she liked them very much because the music didn’t disturb her afternoon nap which she had a habit of taking at this hour. But this time the music was evidently too loud even for her and gave her a fright. All this action took place to the accompaniment of enthusiastic applause from the audience. It was the longest applause I have ever received during my whole singing career. If it was not quite a standing ovation that was only because some of the audience experienced difficulty in getting to their feet without assistance.

Later I received some flowers and thanks and then it gradually dawned on me that I had perhaps received all this applause not as a singer but as a doctor – or maybe both?

Later I received some flowers and thanks and then it gradually dawned on me that I had perhaps received all this applause not as a singer but as a doctor – or maybe both?

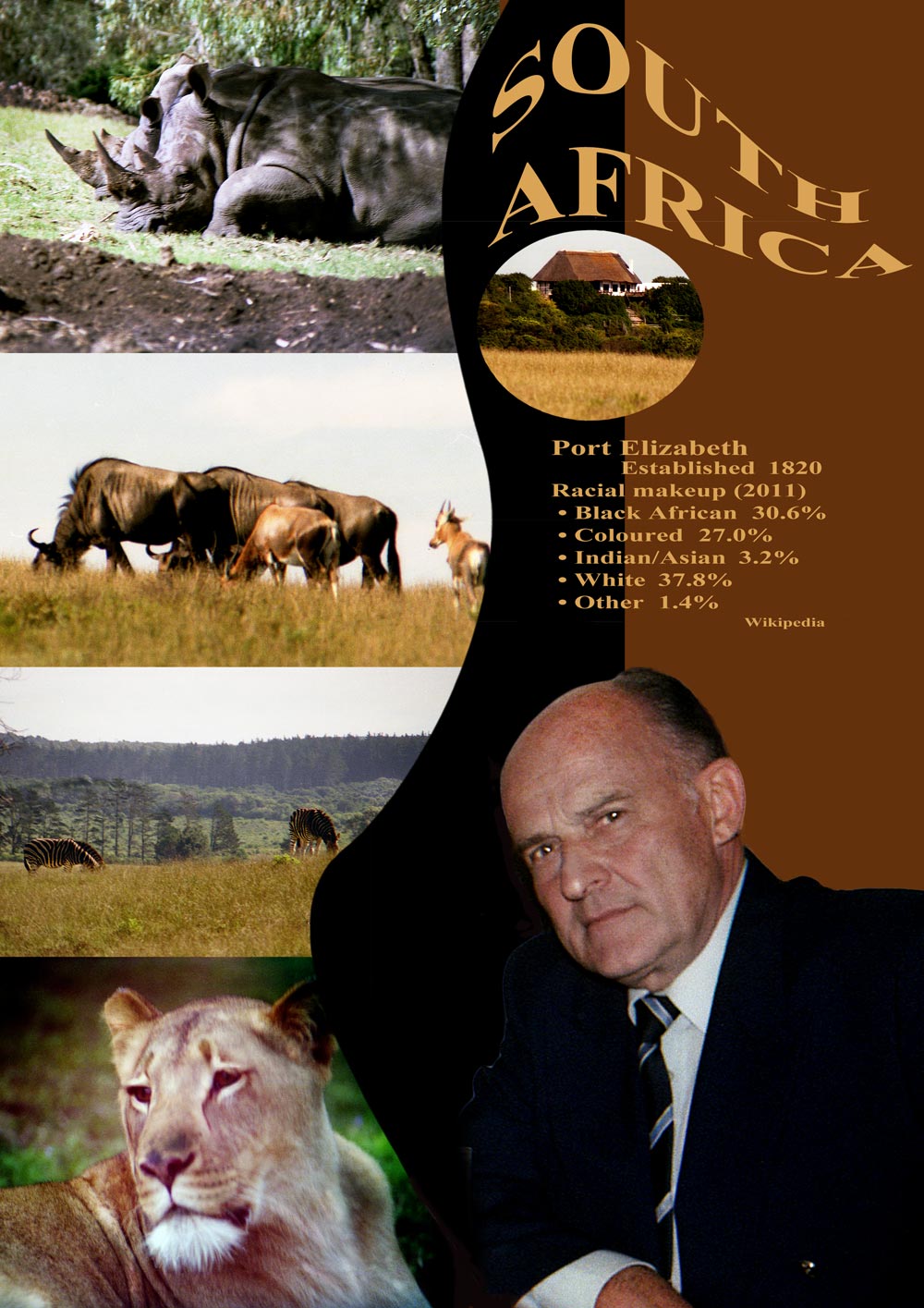

My professional and also vocal careers came to an end in South Africa but not before I had managed to record there almost my entire repertoire on CD or DVD in a professional recording studio to leave them to my children and very few close friends living on different continents, who might have remembered me as a person given to singing all the time.

The last recording I made after a long break was when I was 80 years old and the purpose was to privately celebrate this special birthday and also to prove to myself and to my children that in spite of my advanced age I was still able to sing. If I succeeded it would bring me immense satisfaction, because the majority of professional singers, even the best ones, are usually forced to end their vocal career before reaching my age.

My initial idea was completely different. I decided that to celebrate this specific birthday I would climb a tree. It was not my original idea but something which one of my friends – an old lady – used to do every year on her birthday and she strongly recommended it to me. I accepted her advice enthusiastically. But when the date of my birthday was coming dangerously closer, my uneasiness on inspecting the dendrological state of my garden started to grow. I simply couldn’t find even one tree suitable for my purpose. Most of them were too young and not strong enough to support the weight of my eighty kilograms. Others, which looked taller and stronger like the Yellow-wood had so many small, sharp branches, that they would scratch my skin and cause profuse bleeding before I would get half way up. Of course it was always possible to go to the local park with its many different trees to choose and try my luck there. I had almost accepted this idea as the best solution when suddenly a forgotten picture I had seen many years ago on British television came to my mind. The Fire Brigade, assisted by the Police using high ladders was trying to bring down a cat sitting on one of the branches of a big tree. Evidently the cat had climbed up there by himself and was now too frightened to descend on his own. The TV commentator was explaining to the crowd of onlookers that the poor animal would probably have to spend three days there before his owner, an old lady who was desperately looking for him everywhere, would finally be able to spot him sitting there.

If something like that might happen to me I am sure that the photo of me up in the tree would be on the front page of all local newspapers. And I certainly don’t need such publicity; I told you that I wanted this birthday to be private!

So for my last recording I chose a very romantic song by Tchaikovsky – Amidst the Noise of the Ball, with lyrics by K.Tolstoy, translated into Polish. Unfortunately the recording studio which I had used previously didn’t exist anymore so after a desperate search I finally found a relatively primitive studio, which had been built by the owner of the house for himself and who for this purpose had sacrificed his bathroom and toilet. Their architectural elements and plumbing were still in evidence. I was singing in the converted toilet and through the small soundproof glass window I could see the back of the pianist, who was playing her electronic piano in the bathroom, while the owner of the studio, as a sound engineer, was sitting with his small computer outside in the corridor. I will not provide further details of that recording. It was soon completed and I went home with three CD’s, with three different versions of the song to play them and to choose the best. None of them were acceptable. My voice sounded awful. In two places I was out of tune. I sang the song too slowly and therefore with some kind of unnatural, exaggerated diction. Was it the recording studio, I mean the toilet, which caused me to be so sentimental and melancholic? Several weeks after this unpleasant event and rejection of my recording, late at night, when surfing the internet I found a short fragment of a Russian film, completely unknown to me, showing a ball in Tsarist Russia. The film so beautifully suited the atmosphere of my recorded song that I decided to copy it in order to try later to put it together on a DVD. It took me a lot of work but the final product was excellent. I have shown this DVD to many persons and they loved it. Nobody paid much attention to my singing nor noticed how bad it was. Everybody was concentrating on the pictures. When I asked some of them about the vocal part of this DVD they told me that it was wonderful. They complimented me on having such a youthful voice and for such a subtle interpretation of the song.

I only hope that when Barbara Chodacki illustrates this story with her photographs it will have a similar effect – its literary value will rise and nobody will say that my story is boring. It is especially important now when my reminiscences are beginning to become full confessions for I still want to tell you more about another of my hobbies, which like singing left some visible traces. It is writing.

Many well known writers and also many would-be or might-have-been writers started their literary careers as young or even juvenile poets. They usually wrote love poems to the object of their desire. Some were later ashamed of their literary effusions and hid or even destroyed them. Those who had talent and continued to write poetry in a similar genre were called by literary critics “the great romantic poets” but, if they continued writing poetry in the same style in their later years they were usually described as erotomans.

My own writings – again the hobby of “a writer-amateur” – were not preceded by any attempts at poetry. It started rather unusually by writing and publishing scientific papers. At the time I was working as an orthopaedic surgeon in the Institute of Rheumatology in Warsaw and it was my duty not only to treat and operate on my patients but also to publish papers and deliver lectures for doctors as a part of their postgraduate studies, specialisation etc. During my seven years of working there I published twenty-five such papers in five languages in as many countries which perhaps satisfied fully the scientific needs of my intellect for later, when I moved to another hospital and further till the end of my professional life I did not publish anything connected with medicine. I still continued lecturing and teaching young doctors operating skills and techniques.

Every field of human activity and every profession creates its own language or jargon which is not easily understandable to the general public. I have learned this each time I receive a letter from a bank or other institution and don’t understand what they really want, even when the letter is written in my mother tongue. I suppose that my medical publications were written in such a strange language too. I decided that in order to protect my ability to use “normal” language I must try to write some articles about different topics and send them to various newspapers. So in Poland I wrote twelve such articles, and sent them to different newspapers and to my surprise and satisfaction none of them were rejected.

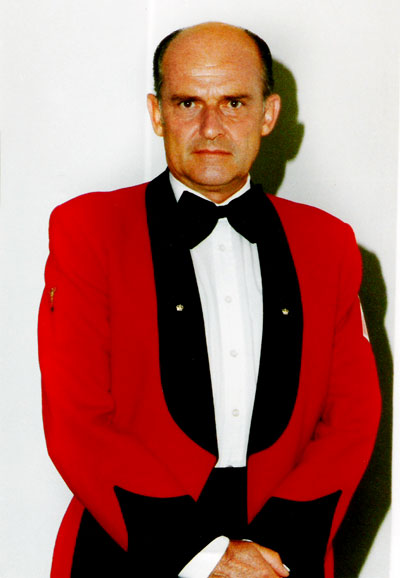

Similarly, in South Africa I wrote twenty-five articles for the Polish magazine published in Cape Town in which I have even had my own column. But the crowning achievement of my writings were two books published in English. As with most of my hobbies the main reason was my curiosity. I asked myself – what is it like to write a book? Is it very difficult? Can I do it? Let me try and see. So I joined the Eastern Province Writers’ Club, wrote several stories, submitted them to competitions in South Africa, received positive feedback and won some prizes. In a few cases I even received a financial award, small in value, but very important to me in giving me encouragement and moral support. Soon the number of stories I wrote reached thirty one – enough, I decided, to put them together in one book under the title Looking Back.

When the book was published I was honoured by the Eastern Province Writers’ Club and received a Special Award for Outstanding Achievement in the form of a diploma which was presented to me during a special meeting of the Club in a local theatre. I framed it and proudly hung it on the wall of my bar, giving in this way a rather misleading impression of the source of my inspiration.

From my readers I received many calls and letters telling me that they had really enjoyed reading my book. Though I value the opinions of my readers very much, I nevertheless have some doubts about their objectivity, because most of them were so called “friendly readers”.

There is a well known saying that everybody can write one interesting book if it is about his own life. As the majority of the stories in my book were based mainly on the events of my life it means that I belong to that category of writers. About such writers people will often say “but he is only a one book writer” which to me doesn’t sound like a compliment. So, after some time I wrote another book Looking Back - Part Two. I hoped that by doing so I might aspire to the next step and become a “two book writer” – which perhaps sounds a little better.

Now, during my retirement when I am doing almost nothing because “I have no time”, I often wonder how it was possible to have done so many things when I was younger. And I haven’t mentioned all of them – there were many other and very different activities in which I was regularly involved every year. There was reading or rather swallowing books, theatre, cinema, social and family life, but also kayaking, canoeing, sailing; climbing mountains, skiing, travelling abroad, keeping dogs training and showing them etc, etc. And of course the main consumer of my time was my job which required many hours of hard work day and night. How much energy and enthusiasm did I have that time, how much curiosity about so many different things? I think that this many-sided interest in too many things was responsible for the lack of serious achievements. I was always only an amateur, if not a dilettante, because I was incapable of concentrating on one or two things only. But it was my nature to be interested in so many things. Without this my life would have been boring.

To be versatile and at the same time successful in everything you, you do not need to be a genius of the calibre of somebody like Leonardo da Vinci but at least to possess a genuine many-sided talents.

When I contemplate the artistic achievements of Barbara Chodacki, what strikes me above all is the totally different way she has pursued her hobby from the way I have pursued mine. Whereas I squandered whatever talents I may have had, Barbara was able to concentrate on one or two areas of interest and follow them through consistently to achieve the highest standards. Hers was no amateur approach but involved selfless and dedicated hard work and continuous self-criticism until she was satisfied with what she had accomplished. Her main sphere of interest was film but it also included the closely related fields of photography, graphics, and posters etc. Her interests and talents were manifest at an early age. As a child she organised theatrical performances with children of her own age. Later she took up photography and made short meaningful sequences of moving pictures accompanied by music. Her first attempts at film making were short films, more like studies and exercises but soon she moved on to documentaries and later still to making full-length feature films.

She has never stopped learning about film making and continuously keeps abreast of the latest trends and developments. The advent of computer technology has given a further boost to her career by enabling her to convert hours of material from her camera to digital formats. By profession she is a pharmacist but in film making she is self-taught and by mastering all the tricks of the trade and learning from her mistakes she has achieved the pinnacle of perfection.

Imagine for a moment that you are watching a film which has just finished. The credits begin to roll – the names of the producer, the director, of the actors, the technicians, the sound operators, the camera-men, and the make-up artists and so on, all experts at what they do. Now imagine Barbara, camera in hand, doing all those jobs single-handedly and you have the measure of her achievement.

It is a matter of regret that she had no opportunity to make films with professional actors but relied only on amateurs, even those with such dubious talents as myself.