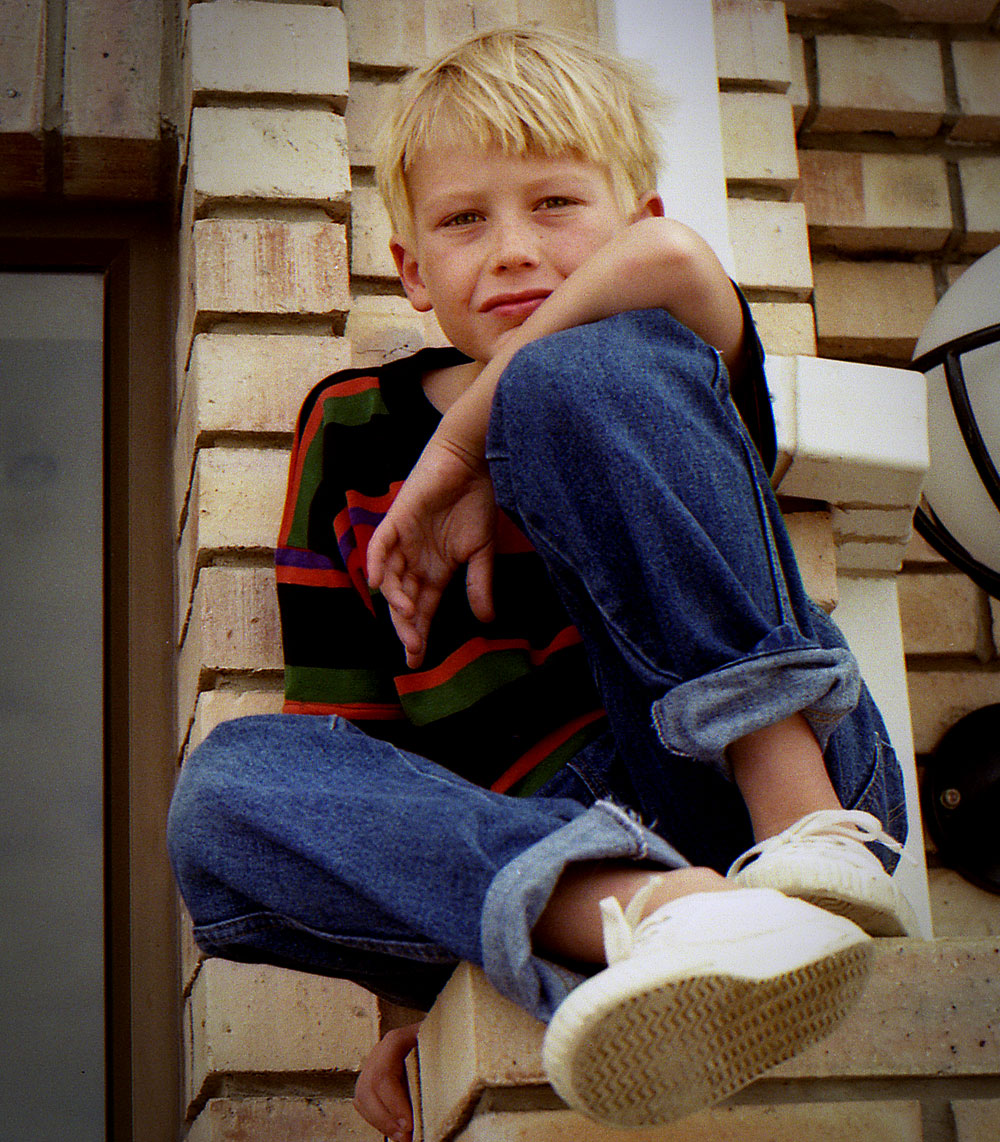

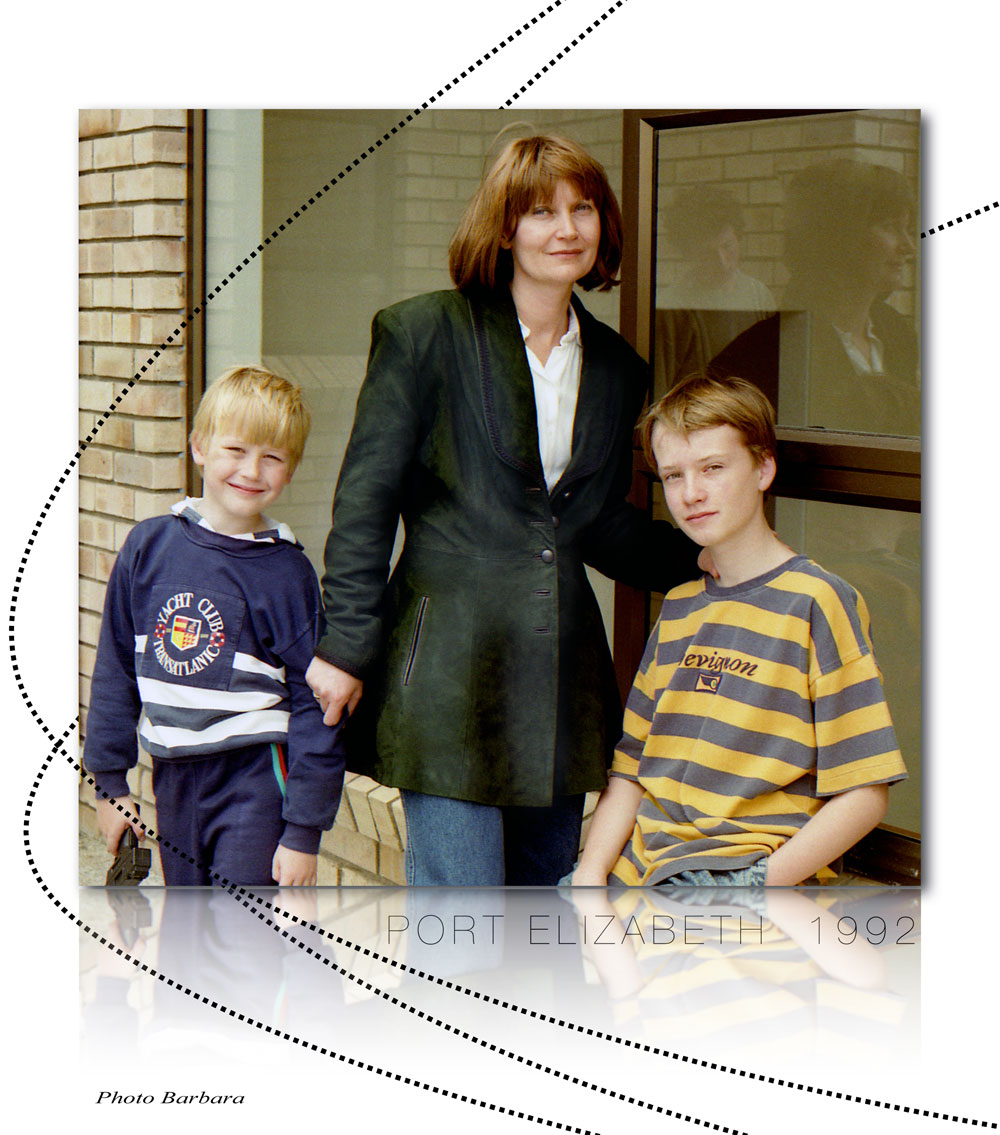

I have known Robert from his early infancy. The events I am going to describe in this story occurred when he was about four or five years old. At the time I called him Robby as his full name seemed to be too serious for a lad of his age and nature. He was the younger son of our two good friends, both doctors and our compatriots. During his childhood I saw him quite often and always admired his physical and acrobatic abilities and his intellectual precocity. The common topic of our discussions was what he would like to be when he grew up. Of course he changed his minds so often that I no longer remember his plans which were usually influenced by events or films he had seen. But one thing never changed – he never wanted to be a doctor.

One day, soon after he had started school, he came with his father to visit us at home while we were entertaining some other friends. To my usual question about what he had in mind for his future, he now told me he was absolutely sure what he wanted to be, a singer. So I asked him to sing something for us. There was no need to repeat my request as is often the case with shy young singers. Robby began his recital with no second bidding and with great confidence. After only a few songs I felt certain that we were listening to an exceptional vocal talent.

I think I know something about singing. As a boy I too wanted to be a singer and sang in several choirs. As a medical student I was still in two minds whether to become a doctor or a professional opera singer. Together with my medical studies I also undertook singing lessons for some years. I also learnt from my many friends among opera singers, singing teachers and students. We often discussed problems connected with singing and these discussions deepened my knowledge, further enriched by reading books and exploiting the resources of the internet.

Unfortunately, my voice lacks the quality to secure me a successful career as a singer although I have given several public performances and have recorded three albums of songs and operatic arias, all of which have been appreciated, even by experts, whatever reservations they may have had about my voice. So I became a doctor and had to be content with being the best singer among orthopaedic surgeons at my hospital, singing performing in an operating theatre rather than an opera house. But I have never lost my interest in vocal music and have developed the habit of listening to opera almost every day as sung by the world’s best singers. All in all, I think I can recognise a vocal talent when I hear one.

What was so special about Robert’s singing? First of all, he had learned all the songs he performed from the radio or television which required a good musical memory, essential for professional singers. Not only the music but also the words in various languages which of course were unfamiliar to him. While singing he was also acting, using body language, gestures and facial expressions. How many top opera singers had failed to learn these skills! Jussi Björling was a classical example of someone who didn’t.

In some songs, Robert had a habit of changing the timbre of his voice, imitating the voices of those he had heard. A mature singer must use his own voice and not parrot somebody else’s. However, students of singing who have this ability to emulate good singers will usually make faster progress in reaching perfection.

As mentioned above, Robert showed no signs of nervousness in front of the audience. He behaved naturally and confidently. Again I remembered how many excellent singers performed below their potential because of terrible stage fright. His natural voice sounded very pleasant and he was able to project it well. I know too well from my own experience that a singer must have a good voice and Robert’s sounded good enough to me. But there was no guarantee that it would mature into a greatone. Boys’ voices can start well but sometimes fail to develop. On the other hand, many opera singers who started off singing in boys’ choirs have continued into advanced old age.

I wouldn’t consider myself some kind of expert if I hadn’t noticed some elementary faults in Robert’s singing. For one thing, he took too much air into his lungs and as a result used it uneconomically. But this common fault can easily be corrected by proper training.

“Yes!” I exclaimed. “Proper training. That’s what he needs. His talent must not go to waste!”

“But…are there any good singing teachers in our town?” asked his father.

“What do you mean by a good teacher?” I turned his question back to him. “A famous retired opera singer? He will teach him nothing. If he was a very good singer, he will probably be useless as a teacher because as a natural singer, he will not appreciate the difficulties other people have. Only a bad singer changed in to a good one by proper training can be a good teacher”.

“Do you know anybody like that here?” asked his father.

“Yes, I do. Myself!” I said. “To start with, Robby must learn only a few elementary things – proper breathing, using his head to improve resonance, learning to sight-read and in addition he must listen to as many recordings of the best singers as possible. That will develop his musicality and aesthetic response towards vocal music. The rest will be done later with a professional teacher with greater experience than mine.”

His father looked almost convinced. Then the question was put to Robert – did he want to?

“Not really” he said. He liked singing but he didn’t want to study it. What he really wanted to do was to learn horse-riding like some of the boys at his school. So as a last resort, I tried to bribe him. That works with most children. I offered him R1 for each lesson and he could have as many lessons as he wanted.

“No thanks” he said.

I increased the bribe to R5 a lesson. He still rejected my offer.

I thought he was too young, too innocent to know the power of money. Maybe I should have tried to bribe him with ice cream instead, though that might be detrimental to his voice. There was nothing more I could do. I would have to wait patiently, I told myself. His vocal training is not an urgent matter and in the meantime his interest in singing might increase or at least his interest in money.

Four months later when I called his parents, Robert answered the phone. As usual, I asked him if he knew what he wanted to do in life.

“Yes, now I’m sure” he said. “I want to sell insurance”.

This was a promising answer because it showed that he had begun to appreciate the value of money so then I asked him whether he was still singing. When he said he was, I repeated my offer of giving him some singing lessons and paying him for them.

“I’ll think about it” was his answer.

He called me just three days later to tell me he was ready to start his vocal training with me and to make fast progress he would need frequent lessons, at least three a week. I was overwhelmed with delight.

“But” he added, “I expect you to pay me R50 per lesson”.

With this demand the hopes of realising our two great “artistic talents” were dashed. I could not agree to pay him that amount of money without declaring bankruptcy in the middle of his training and for a short moment I even began to doubt whether he really possessed that great talent which had fascinated me. But he certainly seemed to have financial talent so perhaps his future lay in that direction.

Later Robert finished school and left to study at university so our contacts became more sporadic. When I met him again after a long interval and asked him whether he was still singing, I learned that he was an active member of several student musical groups and enjoyed popularity as a singer.

Much later I learned that he had emigrated and now lives and works in the Far East and is married. I am still keen to know whether he still sings and although I don’t know the answer I am sure he must do because I have always believed that real talents are never wasted.

Lech Bazylczuk Port Elizabeth 2017

© 2017 Barbara Chodacki. All Rights Reserved.